Filed in

Conferences

Subscribe

Subscribe to Decision Science News by Email (one email per week, easy unsubscribe)

ECONOMIC CONFERENCE ON MARKETING AND CONSUMER PROTECTION

View this announcement online

The Federal Trade Commission’s Bureau of Economics and Marketing Science are co-organizing a one-day conference to bring together scholars interested in issues at the intersection of marketing and consumer protection policy and regulation. As the primary consumer protection law enforcement agency, the FTC has benefited from the marketing literature in its long history of case and policy work. The goal of the conference is to promote an intellectual dialogue between marketing scholars and FTC economists. Specifically, the conference will serve as a vehicle for marketing scholars to learn about the FTC’s practice in consumer protection, promoting potentially high impact research in the area of consumer protection and regulation, and introducing FTC economists to some of the cutting-edge research being conducted by marketing scholars. The conference will feature academic research paper sessions and a panel discussion between FTC economists and marketing scholars.

CONFERENCE PROGRAM

The conference program will run from 8:30 am to 5:30 pm on Friday, September 16, 2016, in the FTC 5th Floor Conference Room at Constitution Center. There will be an optional dinner after the conference starting at 6:00 pm. A fee of $100 will apply to participants who choose to attend the dinner.

Pre-registration for this conference is necessary. To pre-register, please e-mail your name, affiliation, and whether you intend to participate in the conference dinner to marketingconf@ftc.gov (link sends e-mail). Attendees must register for the conference dinner by September 1. Your email address will only be used to disseminate information about the conference. If space permits, we may allow a very limited number of onsite registrations beginning at 8:15 am on September 16.

The scientific committee for this conference consists of:

K. Sudhir, Editor-in-Chief, Marketing Science and Professor of Marketing, Yale School of Management

Avi Goldfarb, Senior Editor, Marketing Science and Professor of Marketing, University of Toronto

Ganesh Iyer, Senior Editor, Marketing Science and Professor of Marketing, University of California, Berkeley

Ginger Jin, Director, Federal Trade Commission Bureau of Economics and Professor of Economics, University of Maryland

Andrew Stivers, Deputy Director, Federal Trade Commission Bureau of Economics

SPONSORS

INFORMS Society of Marketing Science (ISMS)

Federal Trade Commission Bureau of Economics

STAFF CONTACT

Constance Herasingh

202-326-2147

marketingconf@ftc.gov

Those interested in the Marketing Science – Federal Trade Commission Economic Conference on Marketing and Consumer Protection may also be interested in the FTC Workshop: Putting Disclosures to the Test on September 15, 2016.

Filed in

Jobs

Subscribe

Subscribe to Decision Science News by Email (one email per week, easy unsubscribe)

DEADLINE TO APPLY NOVEMBER 1st, 2016

The Operations, Information and Decisions Department at the Wharton School is home to faculty with a diverse set of interests in behavioral economics, decision-making, information technology, information-based strategy, operations management, and operations research. We are seeking applicants for a full-time, tenure-track faculty position at any level: Assistant, Associate, or Full Professor. Applicants must have a Ph.D. (expected completion by June 2017 is preferred but by June 30, 2018 is acceptable) from an accredited institution and have an outstanding research record or potential in the OID Department’s areas of research. The appointment is expected to begin July 1, 2017.

More information about the Department is available at:

https://oid.wharton.upenn.edu/index.cfm

Interested individuals should complete and submit an online application via our secure website, and must include:

• A curriculum vitae

• A job market paper

• (Applicants for an Assistant Professor position) Three letters of recommendation submitted by references

To apply, please visit this web site:

https://oid.wharton.upenn.edu/faculty/faculty-recruiting/

Further materials, including (additional) papers and letters of recommendation, will be requested as needed.

To ensure full consideration, materials should be received by November 1st, 2016.

Contact:

OID Department

The Wharton School

University of Pennsylvania

3730 Walnut Street

500 Jon M. Huntsman Hall

Philadelphia, PA 19104-6340

The University of Pennsylvania is an affirmative action/equal opportunity employer. All qualified applicants will receive consideration for employment and will not be discriminated against on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, national origin, disability status, protected veteran status, or any other characteristic protected by law.

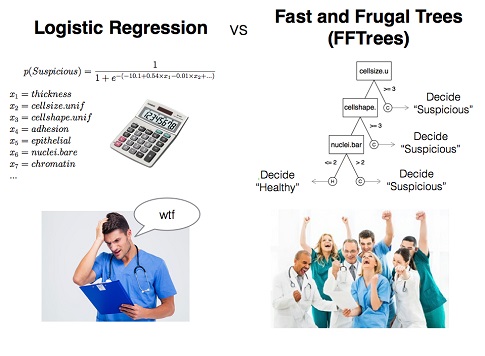

CLASSIC HEURISTICS AND DATA SETS ALL IN ONE TIDY PACKAGE

It just got a lot easier to simulate the performance of simple heuristics.

Jean Czerlinski Whitmore, a software engineer at Google with a long history in modeling cognition, and Daniel Barkoczi, a postdoctoral fellow at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development, have created heuristica: an R package to model the performance of simple heuristics. It comprises the heuristics covered in the first chapters of Simple Heuristics That Make Us Smart such as Take The Best, Unit Weighted Linear model, and more. The package also includes data, such as the the original German cities data set which has become a benchmark for testing heuristic models of choice, cited in hundreds of papers.

A good place to start is the README vignette, as with vignettes:

Here’s the heuristica package’s home on CRAN and here’s a description of the package in the authors’ own words:

The heuristica R package implements heuristic decision models, such as Take The Best (TTB) and a unit-weighted linear model. The models are designed for two-alternative choice tasks, such as which of two schools has a higher drop-out rate. The package also wraps more well-known models like regression and logistic regression into the two-alternative choice framework so all these models can be assessed side-by-side. It provides functions to measure accuracy, such as an overall percentCorrect and, for advanced users, some confusion matrix functions. These measures can be applied in-sample or out-of-sample.

The goal is to make it easy to explore the range of conditions in which simple heuristics are better than more complex models. Optimizing is not always better!

Filed in

Gossip ,

Ideas

Subscribe

Subscribe to Decision Science News by Email (one email per week, easy unsubscribe)

PUTTING OUR MONEY WHERE OUR MOUTH IS

Click to enlarge

Some experts seem pretty sure Donald Trump will be the next US President. Michael Moore wrote an article entitled 5 Reasons Why Trump Will Win.

Prediction maven Nate Silver has warned a few days ago “Don’t think people are really grasping how plausible it is that Trump could become president. It’s a close election right now.”

Despite this, we think that Hillary Clinton is going to win.

And we’ve put our money where our mouth is. There’s a prediction market called PredictIt in which US citizens in most states can legally bet on events happening or not. There’s an $850 limit on any contract, but you can get around that, in the following way.

As the figure up top shows, we’ve placed two bets:

- We bet $799.50 that the next President will not be a Republican. That is, we bought 1250 shares of “no” on that contract at 65 cents each. If the next President is indeed not a Republican, we’ll be able to sell those shares for a dollar each, or $1230. Otherwise we lose our money.

- We bet $849.87 that Hillary Clinton will be the next President. That is, we bought 1349 shares of “yes” on that contract at 63 cents. If Hillary wins, we’ll be able to sell our shares for $1349. Otherwise we lose our money.

So, we’ve bet $1,649.37. If Hillary wins, we’ll have $2,579 (minus the market’s 10% fee on profits). If Trump or some other Republican wins, we’ll have bupkis.

Filed in

Conferences

Subscribe

Subscribe to Decision Science News by Email (one email per week, easy unsubscribe)

CALL FOR PAPERS. SUBMISSION DEADLINE AUG 26, 2016

This winter, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) will host its second research conference on consumer finance.

We encourage the submission of a variety of research. This includes, but is not limited to, work on: the ways consumers and households make decisions about borrowing, saving, and financial risk-taking; how various forms of credit (mortgage, student loans, credit cards, installment loans etc.) affect household well-being; the structure and functioning of consumer financial markets; distinct and underserved populations; and relevant innovations in modeling or data. A particular area of interest for the CFPB is the dynamics of households’ balance sheets.

A deliberate aim of the conference is to connect the core community of consumer finance researchers and policymakers with the best research being conducted across the wide range of disciplines and approaches that can inform the topic. Disciplines from which we hope to receive submissions include, but are not limited to, economics, the behavioral sciences, cognitive science, and psychology.

The conference’s scientific committee includes:

- Adair Morse (University of California Berkeley, Haas School of Business)

- Annette Vissing-Jorgensen (University of California Berkeley, Haas School of Business)

- Colin Camerer (California Institute of Technology)

- Eric Johnson (Columbia University, Columbia Business School)

- Jonathan Levin (Stanford University)

- Jonathan Parker (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Sloan School of Management)

- José-Victor Rios-Rull (University of Pennsylvania)

- Judy Chevalier (Yale School of Management)

- Matthew Rabin (Harvard University)

- Susan Dynarski (University of Michigan)

Authors may submit complete papers or detailed abstracts that include preliminary results. All submissions should be made in electronic PDF format to CFPB ResearchConference at cfpb.gov by Friday, August 26th, 2016.

Please remember to include contact information on the cover page for the corresponding author. Please submit questions or concerns to Worthy.Cho at cfpb.gov.

Filed in

Ideas ,

R

Subscribe

Subscribe to Decision Science News by Email (one email per week, easy unsubscribe)

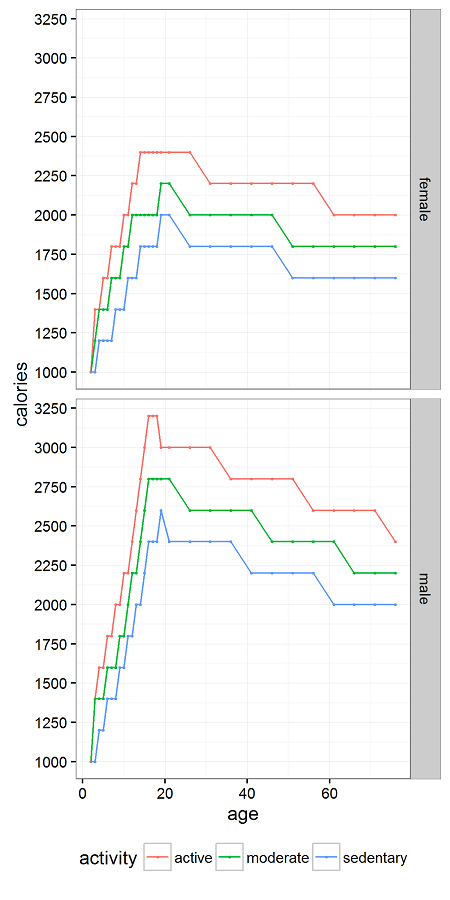

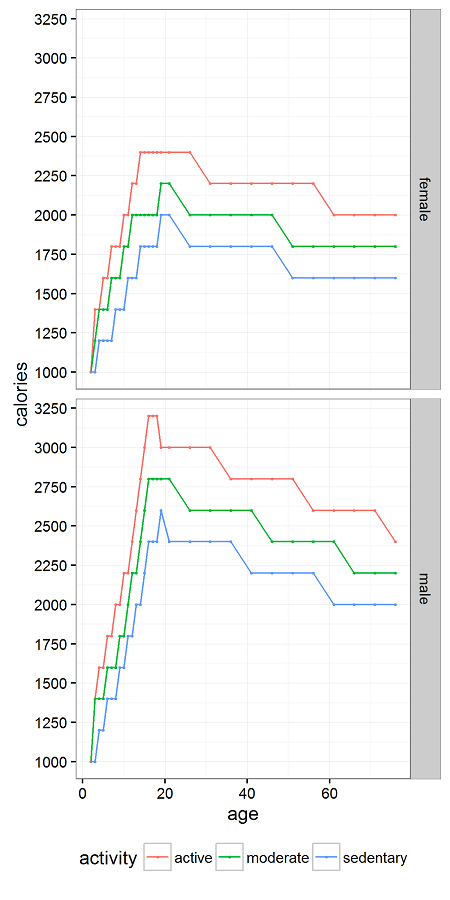

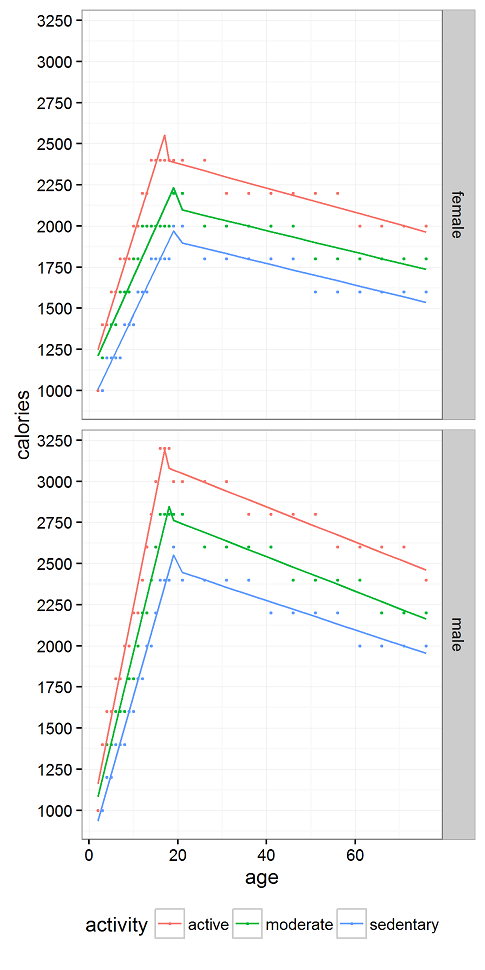

US GOVERNMENT GUIDELINES BY AGE, SEX, ACTIVITY LEVEL

Click to enlarge

At Decision Science News, we are always on the lookout for rules of thumb.

Our colleague Justin Rao was thinking it would be useful to express calories as a percentage of daily calories. So instead of a coke being 150 calories, you could think of it as 7.5% of your daily calories. Or whatever. The whatever is key.

This is an example of putting unfamiliar numbers in perspective.

So, we were then interested to see if there would be an easy rule of thumb for people to calculate how many calories per day they should be eating, so that they could re-express foods as a percentage of that.

We found some calorie guidelines on the Web published by the US government. With the help of Jake Hofman, we used Hadley Wickham‘s rvest package to scrape them and his other tools to process and plot them.

The result is above. If you have any ideas on how to fit it elegantly, let us know.

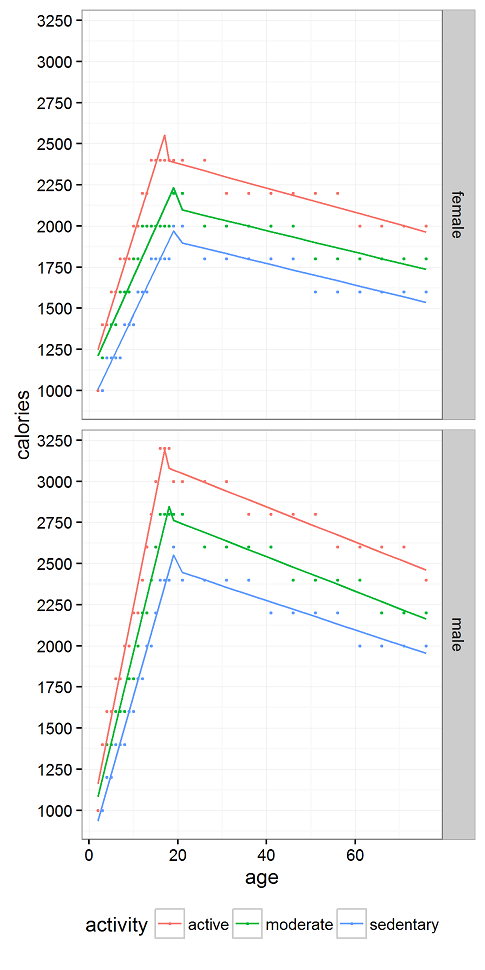

We tried a number of fits. Lines are good for heuristics, so we made a bi-linear fit to the raw data (in points). We’re all grownups reading this blog, so let’s focus on the lines to the right of the peak.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Time to make the heuristics. For women, you need about 65 fewer calories per day for every decade after age 20. For men, you need about 105 fewer calories per day for every decade after age 20. Or let’s just say 70 and 100 to keep it simple.

So, if you have an opposite sex life partner (OSLP?), keep in mind that you may need to cut back by more or fewer calories as the person across the table as you age together. Same sex life partner (SSLP?), cut back the same amount. Just don’t go beyond the range of the chart. The guidelines suggest even sedentary men shouldn’t eat fewer than 2,000 calories a day at any age. For women, that number is 1650.

REFERENCES

Barrio, Pablo J., Daniel G. Goldstein, & Jake M. Hofman. (2016). Improving comprehension of numbers in the news. ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’16). [Download]

The R code, below, has some other attempts at plots in it. You may be most interested in it as a way to see rvest in action. Or just to get the data.

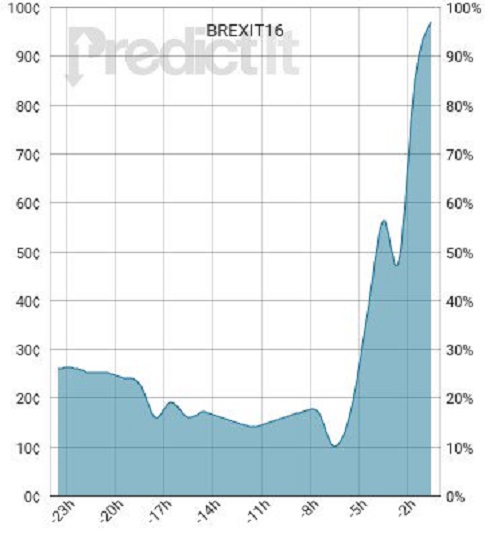

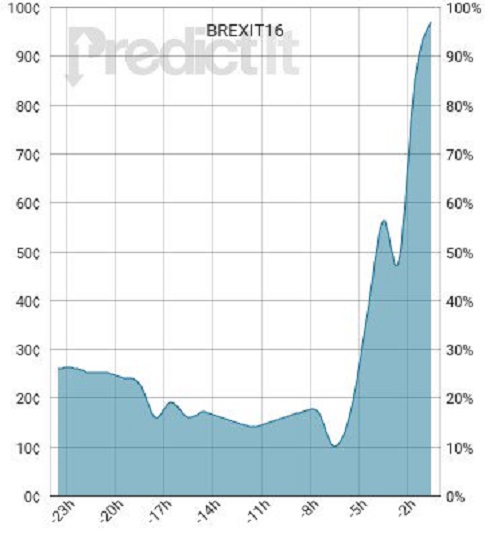

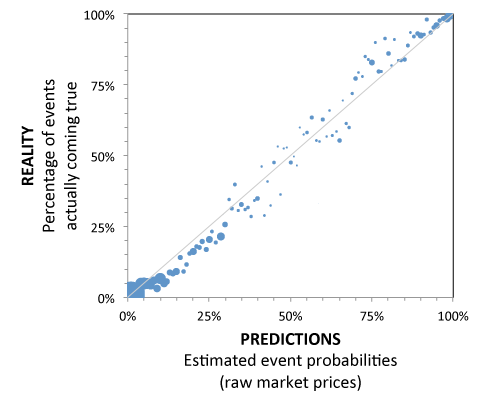

PREDICTION MARKETS NOT AS BAD AS THEY APPEAR

Two recent events in the UK made it look like prediction markets’ predictions aren’t worth much.

The soccer team Leicester City won the premiere league title despite the markets putting the odds of them doing so at 5,000 to 1 (.02%).

Last week, people in the UK, voted to leave the European Union. A few hours before it was sure they would exit, a prediction market put their probability of leaving at 10%. See the figure above from PredictIt. X axis is roughly time before the outcome was certain. Y axis can be interpreted as probability of exit (70 cents = 70%). It jumped from 10% to 90% in just five hours.

Analysts like to “explain” market results, coming up with a reason why an event was a failure of the prediction market. For instance, in the two events above, the Wall Street Journal, perhaps correctly, claims the bets were unduly influenced by London bettors. Through big London bets the odds moved to reflect what Londoners believe instead of the sentiment of the crowd. In predicting a Brexit, the sentiment of the crowd is exactly what you want.

Whenever the prediction market is far on the wrong side of 50%, explanations will arise as to why the prediction market was wrong. Let’s take a step back here.

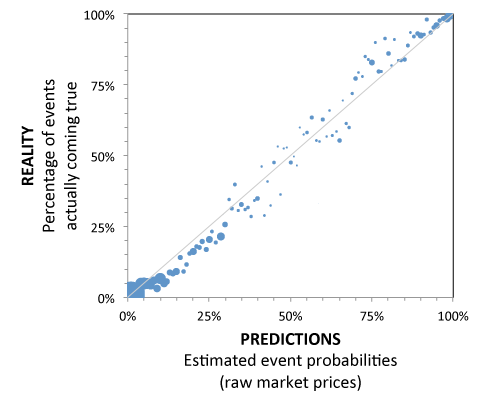

A desirable property of a prediction market is that it is calibrated. To be calibrated, events that it predicts to be 90% likely should occur 90% of the time. Events that it predicts to be 10% likely should occur 10% of the time.

If events that it predicts to be 10% likely (e.g. Brexit) occur 0% of the time, the prediction market has a problem. It is over-estimating the chances.

Looking at the calibration of prediction markets across many events, one will see that they are typically very well calibrated. Take, for instance that Hypermind prediction market. The figure below shows close to 500 events that it predicted. If the market were perfectly calibrated, the points would fall along the diagonal line (i.e., 10% likely events would happen 10% of the time, 20% likely events would happen 20% of the time, and so on).

It’s very well calibrated. Here’s a similar chart for U.S. primaries at PredictWise.

So the next time a market “misses” a 10% prediction, let us keep in mind that it needs to miss 10% of those predictions to stay calibrated. As the Émile Servan-Schreiber mentions in this post, “It is perhaps a bit ironic to note that the data from the Brexit question slightly improved [the prediction market’s] overall calibration. It is as if the occurence of an unlikely event was long overdue in order to better match predicted probabilities to observed outcomes!”

You may wish that that prediction markets had prefect calibration and predicted only 0% or 100%. We do, too. But the world is an imperfect place.

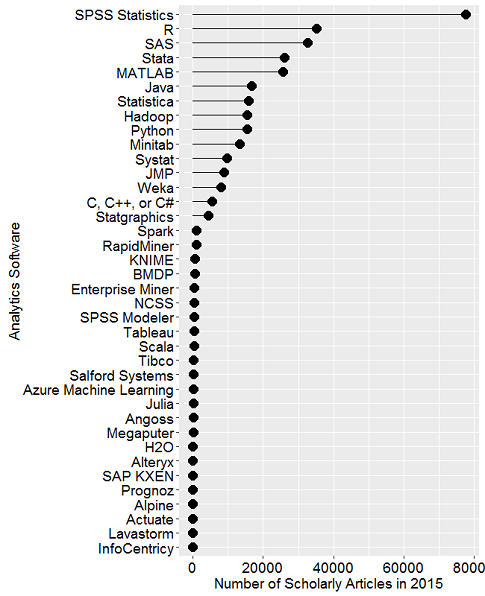

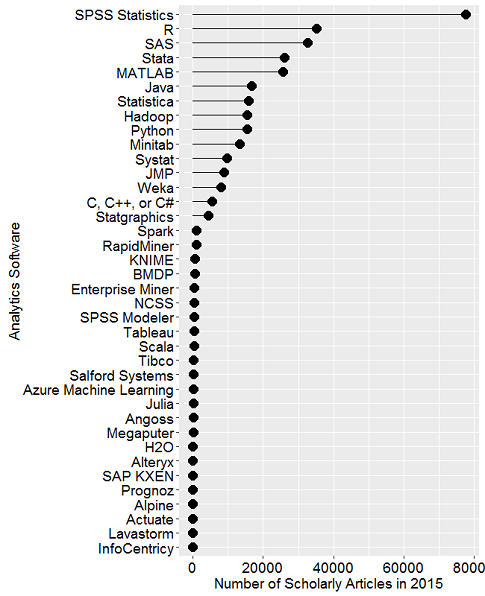

WE THOUGHT IT WAS NUMBER ONE

Robert Meunchen has done a rather in depth analysis of the popularity of various packages for statistical computation. More detail here.

We were surprised to see that R has passed SAS for scholarly use. We were surprised because we assumed this would have happened years ago. Meunchen too predicted it would have happened in 2014.

In addition, we were surprised to see that SPSS holds the number one spot, and by a fair margin. We can only think of one person who uses SPSS.

Perhaps we’re guilty of false consensus reasoning.

A chart further down the post shows that Python is rapidly growing in use. That meshes with what we observe. Many of our PhD student interns come in using Python for data analysis. One who I worked with, Chris Riederer, is even writing a version of dplyr in Python and calling it dplython, of course.

Subscribe to Decision Science News by Email (one email per week, easy unsubscribe)

Subscribe to Decision Science News by Email (one email per week, easy unsubscribe)