Trust has a substitute?

Subscribe to Decision Science News by Email (one email per week, easy unsubscribe)

Subscribe to Decision Science News by Email (one email per week, easy unsubscribe)

TRUST BUT VERIFY: MONITORING IN INTERDEPENDENT RELATIONSHIPS

Effective organizations depend upon employees who will rely upon each other even when they do not trust each other. How then can managers promote trustworthy behavior to maintain the effectiveness of their organizations? Managers, employees, and customers routinely rely upon others to choose trustworthy actions. Managers trust that employees will complete work, employees expect that they will be paid, and customers expect goods and services to be delivered on time. Trust reduces transaction costs, improves efficiency of economic transactions, and enables managers to negotiate more efficiently and lead more effectively. A trusting environment, though, is not necessarily the norm. In many organizational settings, including negotiations and accounting, people routinely engage in untrustworthy and unethical behavior. The effect of this kind of behavior on trust has been demonstrated in numerous studies, which identify various individual and contextual factors that influence trust. One such study employing repeated prisonerâs dilemma and ultimatum games found that responders were more likely to reject offers proposed by those that had previously used deception in the past. What then can a manager do when trust is low? Monitoring is one approach. For example, some managers randomly administer drug tests, conduct audits and even listen in on phone calls. Between 1990 and 1992 over 70,000 US companies purchased surveillance software at a cost of more than $500 million (Aiello, 1993). Although popular, what are the relationships between different monitoring systems and the actions people choose? A recent article by Maurice E. Schweitzer and Teck H. Ho examines the dynamics of monitoring. They find that frequent monitoring generally increases trust-like behavior. When monitoring is anticipated, trust-like behavior is increased: monitoring is a substitute for trust. However, the study finds that people are particularly untrustworthy when monitoring is unanticipated. In short, monitoring is difficult to turn off once initiated.

ABSTRACT:

“For organizations to be effective, their employees need to rely upon each other even when they do not trust each other. One tool managers can use to promote trust-like behavior is monitoring. In this article we report results from a laboratory study that describes the relationship between monitoring and trust behavior. We randomly and anonymously paired participants (n=210) with the same partner, and had them make 15 rounds of trust game decisions. We find predictable main effects (e.g., frequent monitoring increases trust behavior) as well as interesting strategic behavior. Specifically, we find that anticipated monitoring schemes (i.e., when participants know before they make a decision that they either will or will not be monitored) significantly increase trust behavior in monitored rounds, but decrease trust behavior overall. Participants in our study also reacted to information they learned about their counterpart differently as a function of whether or not monitoring was anticipated. Participants were less trusting when they observed trustworthy behavior in an anticipated monitoring period than when they observed trustworthy behavior in an unanticipated monitoring period. In many cases, participants in our study systematically anticipated their counterpartâs untrustworthy behavior. We discuss implication of these results for models of trust and offer managerial prescriptions.”

QUOTES:

“While prior work has argued that trust is an essential ingredient for managerial effectiveness (Atwater, 1988), many relationships within organizations lack trust. For example, managers within large organizations with high turnover may not have sufficient time to develop trust among all of their employees. Even in the absence of actual trust, however, managers need to induce trust-like behavior. In this article we conceptualize monitoring as a substitute for trust, and we demonstrate that monitoring systems significantly influence trust-like behavior.”

“We conceptualize monitoring as a tool to produce trust-like behavior, and we consider ways in which monitoring changes incentives for engaging in trust behavior. We adopt a functional view of trust by assuming individuals calculate the costs and benefits of engaging in trust behavior in a manner consistent with Ajzenâs (1985, 1987) theory of planned behavior. In particular, we focus on the role of monitoring systems in altering the expected costs and benefits of choosing trust-like actions. This conceptualization matches our experimental design, because participants in our study are paid for their outcomes and remain anonymous to their counterpart. There is no way for participants to find out who their partners are, and as a result, participants in our study face a well-defined “shadow of the future” defined by the future rounds of a repeated trust game.”

“Consider monitoring regimes that range from one extreme, complete monitoring, to another extreme, no monitoring. Under complete monitoring, participants have an incentive to exhibit trust-like behavior, especially in early rounds, because their counterpart will observe their actions and can reciprocate in future rounds. On the other hand, under no monitoring, participants have little incentive to engage in trust-like behavior, because their counterpart cannot observe their actions. In this case, the expected benefits of choosing untrustworthy actions exceed the expected benefits of choosing trust-like actions. If players are self-interested, opportunism is likely to prevail. The more frequent the monitoring, the greater the expected benefits of choosing trust-like actions. Consequently, we hypothesize that monitoring frequency will be positively correlated with trust-like behavior. With more frequent monitoring, untrustworthy behavior is more likely to be detected and subsequently punished or reciprocated. As a result, if players are calculative and maximize their total payoff for the entire interaction, they will exhibit more trust-like behavior when they experience more frequent monitoring.”

“[A]nticipated monitoring schemes decrease trust- like behavior in periods of no monitoring by harming trust development. Players who observe others choosing trustworthy actions in anticipated monitoring periods may attribute the trustworthy behavior they observe to the monitoring scheme rather than the trustworthiness of the individual. As a result, players who observe trustworthy behavior in anticipated monitoring periods may be less likely to assume that their counterpart will choose trustworthy actions when they are not monitored. As a result, trustworthy actions are less diagnostic of true trustworthiness and less effective in building trust when the observed trust behavior occurs in an anticipated period of monitoring. For both of these reasons, we hypothesize that anticipated monitoring will decrease trust-like behavior in non-monitored rounds.”

“First, we find that frequent monitoring increases overall trust-like behavior. Second, we find that anticipated monitoring harms overall trust-like behavior, but significantly increases trust-like behavior for periods in which monitoring is anticipated; in our study, Even players were particularly trustworthy in anticipated monitoring rounds, but were particularly untrustworthy when they anticipated no monitoring.”

ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

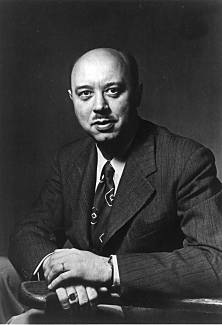

Maurice E. Schweitzer

“

“Maurice E. Schweitzer is assistant Professor of Operations and Information Management at The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. He received his PhD the University of Pennsylvania in 1993. His research interests include deception and trust, negotiations and behavioral decision research. Currently he is working on projects involving the influence of emotions on trust, trust recovery, envy and unethical behavior and Insurance fraud.

Maurice E. Schweitzer Home Page at Wharton

Teck H. Ho

Teck H. Ho is the William Halford Jr. Family Professor of Marketing Executive Director at the Berkeley Experimental Social Sciences Laboratory (Xlab). He received his PhD from in Decision Sciences from The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania in 1993. His research interests current projects involve B2B contract design, Strategic IQ and trust building.

Teck H. Ho Homepage at The University of California at Berkeley.